Postcard from Vilnius: Welcome to the Republic of Užupis

I visit the community of Užupis, and stumble into a self-proclaimed republic for writers, artists, and renegades in the heart of Vilnius, Lithuania's cultured and compact capital city

Postcard from Vilnius: Welcome to the Republic of Užupis

I visit the community of Užupis, and stumble into a country for writers, artists, and renegades in the heart of Vilnius, Lithuania’s cultured and compact capital

Welcome to the Republic of Užupis. CREDIT:

Postcard from Vilnius: Welcome to the Republic of Užupis

The cobblestone path leads you away from centuries’ old fortified walls, to a small bridge over a gentle winding river.

Ornate, wrought-iron railings fringe the crossing. A sign in five languages reads: Užupio Res Puublika.

The Republic of Užupis.

Where on earth, you may fairly ask, is that?

The answer is Vilnius. Lithuania’s compact and cultured capital.

Or, to be clear, situated on the edge of Vilnius. For The Republic of Užupis has declared itself to be a republic.

A counterculture commune with its own constitution, national holidays, flag, currency, president and cabinet. In an area covering less than a single square kilometre.

Careful to avoid the puddles, I walk across the bridge, over the River Vilnele from Vilnius old town, to the community of Užupis, into a country for writers, artists, and renegades.

Užupis means ‘beyond the river’ in Lithuanian. A place withheld from the rest of the city by the geographical contours of the flowing, but tame water.

At the other side of the bridge, in the Republic of Užupis, is an unprepossessing, low-slung, caramel coloured building that informs the visitor it serves as a ‘Border Post’.

A flag hangs on the outside wall. A white hand on a red background. There are four flags for this republic. One hand for each season of the year. Blue is winter, green is spring. Yellow represents summer, while autumn is red.

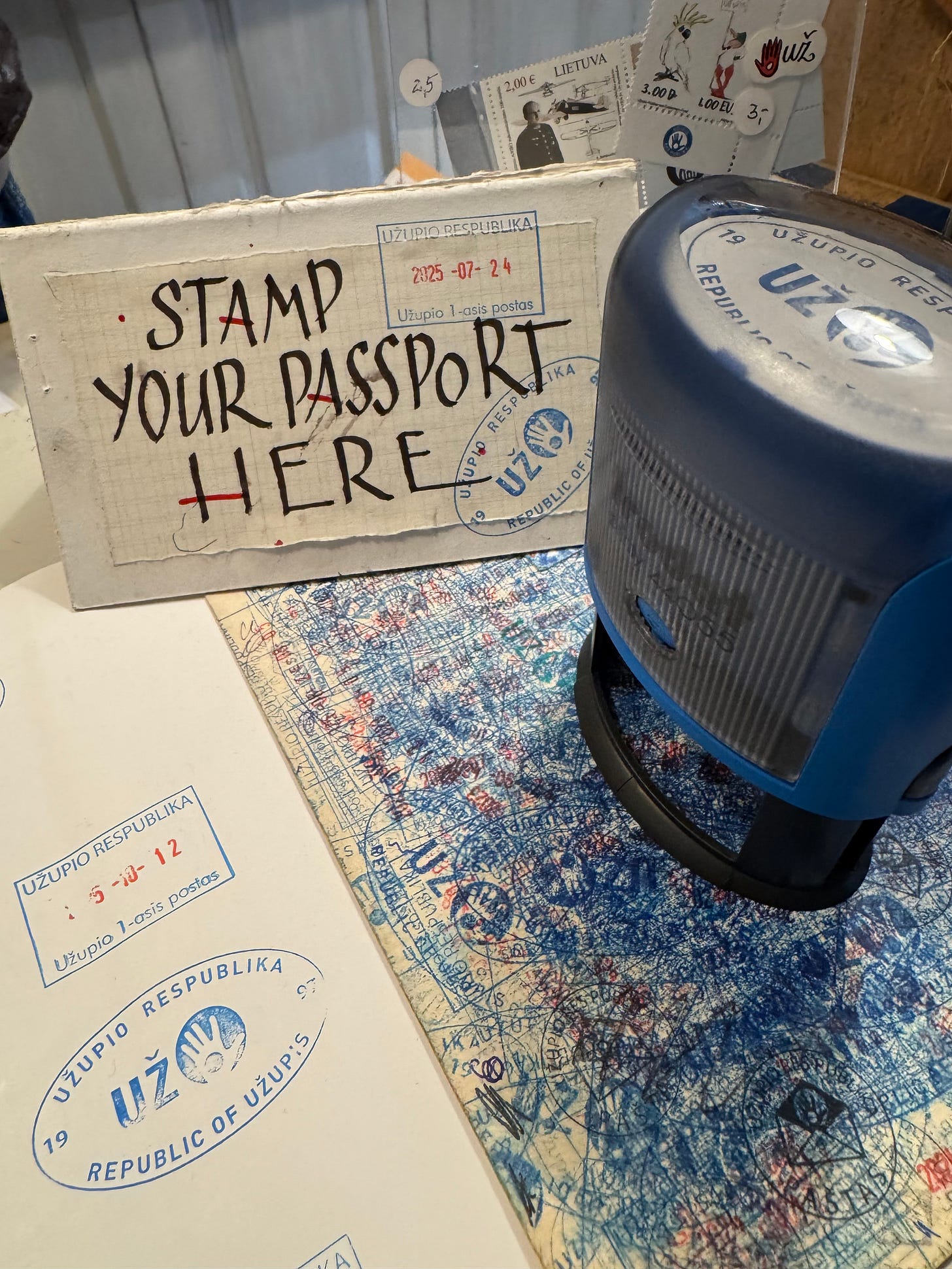

I enter the building. The first thing I see is a sign that says: ‘Stamp your passport here’.

Struggling for confirmation this is not real, knowing the answer, yet still I blurt out inadvertently loud enough for people to hear in the busy border control/flea market/gift shop: “This has got to be a joke, surely?”

“We take our humour very seriously,” a woman quickly replies.

She was right. What started as an ironic April Fools’ Day joke back in 1987 for a small group of artists and bohemians is now a serious business. Including its constitution which has 38 articles.

“You know our constitution?” the woman asks me.

“I’d like to say yes, but, seeing as five minutes ago, I hadn’t even heard of this place, I have to say no,” I reply, as honestly as I could.

The woman with dark curls say immediately, and with no little pride. “The republic celebrates its independence every year on April Fools Day known as Užupis Day.”

She explains there are 38 articles in its constitution, including: Unprompted, she shares further: “Everyone has the right to be happy - number 16.

“And number 17: ‘Everyone has the right to be unhappy.’”

There is a serious, practical side to it all. The area was traditionally a haunt for subversives to meet during the Soviet era, with many creatives still squatting in abandoned buildings, with very few, if any, amenities.

“Which is why number 2 is ‘Everyone has the right to hot water, heating in winter, and a tiled roof,’” she confides to me.

However, the woman cautioned regarding having your passport stamped here in the Republic of Užupis, saying: “You could have conflict and confusion if you go to USA.

“My friend went to New York. Man on desk looks through passport and asks: ‘where is Republic of Užupis?’”

The thought of unsmiling US border guards grilling me on the finer details of the Republic of Užupis when attempting to gain entry to the 2026 World Cup in America next summer, I decide against having my passport stamped.

I didn’t find Frank Zappa but there is the trumpet-blowing angel of Užupis in the main square of the Republic of Užupis. CREDIT:

After buying a t-shirt with the constitution printed on it, I stroll into the renegade republic, along a cobblestoned street, lined with eclectic shops and galleries, selling everything from pop-art, to pink flower pots.

In 1995, during the uncertain aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall six years earlier, artists put up a statue of the legendary Frank Zappa in the main square.

Despite the fact the prog-rock hero had never visited, the iconic songwriter, musician and activist was seen as a powerful symbol of freedom and democracy. Two years later, on April 1, 1997, the commune’s leadership went further, declaring their neighbourhood of Užupis independent from the rest of Lithuania.

I look for Zappa’s statue in the jumbled main square. I fail to find him.

I ask a man with salt and pepper coloured grey stubble, grey hair in a bun, and wearing thin, round metal rimmed glasses, who was smoking a roll-up.

He looks me up and down before intimating that Zappa could be in Tibet Square, named after the Dali Lama’s visit in 2013.

What is undeniably in the outre square is the winged, trumpet-blowing Mermaid of Užupis, standing proudly atop her concrete perch.

A siren for like-minded souls to whom the courteous but candid constitution attracts.

Locals insist if you stare into the eyes of the Užupis Mermaid, you’ll never want to leave. Not least when on April 1 every year, free beer flows from a mini mermaid in the main square.

Later on, after I exit the republic, sitting in a coffeeshop that played Pink Floyd and sold elegant lattes, I tale a look at the constitution and its egalitarian details.

Do not defeat is one. Do not fight back is another. Along with Do not surrender.

There are also the mottoes Everyone has the right to understand (No23). Everyone has the right to understand nothing. (No24).

I particularly like No10, and No11, which are: “Everyone has a right to love and take care of the cat.” With the latter insisting: “Everyone has a right to look after the dog until one of them dies.”

While No13 said rightly: “A cat is not obliged to love its owner, but must help in time of need.” While No12 had existential vibes with: ‘A dog has the right to be a dog.’ Which could work for so many reasons, on so many levels.

But perhaps, my favourite is No21, which reads: “Everyone has a the right to appreciate their own unimportance.”

……..

Fridge magnets. The Republic of Užupis. CREDIT: